Reconstructed Sindarin Pronominal System

A new theory

Initial Thoughts

• From the attested examples of the Corpus, the derivation of new personal pronouns seems to follow a general pattern. When we look at nîn besides lín and mín or ten besides men and even nin it seems clear that there is a distinct basic shape for each case, nominative, dative and possessive to which is added a characteristic consonant.

Demonstratives and neutral forms, on the other hand, seem to have a base form which displays singular and can completely regularly be formed into plural as well, which seems to be what Tolkien originally planned even for the personal pronouns as they can be found for his early Noldorin (which are used in the movie-dialogues).

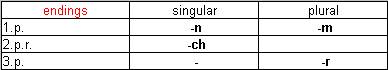

• From the examples of nin and nîn besides conjugation-ending –n for 1.p.sg. and men and mín besides conjugation-ending –m for 1.p.pl. it seems likely that the characteristic consonant is the same that is added for conjugating verbs, which makes a reconstruction easier.

• A form that often seems not to follow those ‘rules’ is the 1.p.sg. This is, however, not a big problem because the conjugation of a-stem verbs is also irregular during conjugation for the 1.p. (ie. the irregular change of final –a to –o in conjugation of a-stem verbs)

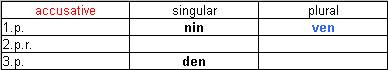

• We have den attested in an accusative context, where, if we follow the general ‘rules’ of Sindarin phonology we could clearly expect lenition. It seems, therefore, logical to conclude that the original form must have been ten; and now matching this with dative men I think it can be expected that for the accusative case, the normal dative pronouns are used in a lenited form.

• I tend to believe that we have two separate forms of 3.p pronouns based off of gender. These are (IMHO) a Masculine/Feminine combination and Neuter/Neutral combination. The fact that we have hain attested in LOTR seems to support this theory.

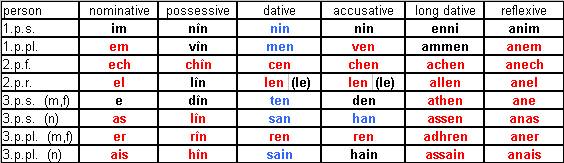

The following is an attempt to explain some of the reasoning for the large chart at the bottom of this page. Sindarin words in blue are unattested, but can be easily reconstructed from the corpus. Words in red are completely unattested.

Personal pronouns

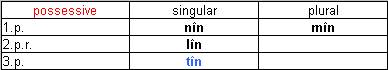

Possessive Pronouns

Most of the known pronouns are possessive so I will list them first because it will make coming reconstructions easier. I do not think there should be seen a difference between í and î, I expect the first as an older form.

Tîn is attested in the corpus as dîn. We see this form multiple times in The Kings Letter. It must be a lenited form because it is used an an adjective to describe to who something/someone belongs. Sellath dîn “his daughters”, ionnath dîn “his sons”, bess dîn “his wife”.

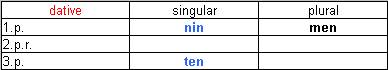

Dative Pronouns

Next are the dative forms which shall be listed here with the accusative forms for the above mentioned reason:

men is only attested in ammen …. an men (for us) and by the shape we can expect it to be dative (refer to den). Another hint to this might be enni … an nin [?] (to me) while anim … an im, using a nominative pronoun, is translated as for myself (clearly reflexive and will be discussed in its own due time). The changed vowel of 1.p.sg. nin (e>i) might be seen as the almost expected irregularity, similar to that of a>o with Sindarin pronominal endings. Now, matching up with possessives, it is easy to fill in the gap of 2.p.sg. as len. This clearly corresponds to the attested le (to thee) which is said to be of Quenya origin, so we can expect len to be the pure Sindarin-counterpart. Whether this form should be used in actual Sindarin writings is hard to say. We know that le was present in the dialect of Imladris, but does this mean it would have taken the place of len in all third age Sindarin? I do not think it is possible to say at this time with our small corpus. Future publishings will hopefully shed more light on this subject.

Concerning the use of san, sain: While we do not readily have evidence to prove otherwise, it seems logical to conclude that these must be neutral pronoun forms instead of masculine/feminine. The fact that we have e, den and dîn all attested as third person forms in the corpus, makes it hard to otherwise fit these in phonologically. These may,therefore, be neutral forms; which could feasibly behave in a separate manner from the other pronoun forms. The only evidence against this proposition seems to come from Ae Adar nín which translates den as “it” which seems to indicate that there is no differentiation between masculine, feminine or neutral forms. I am, however, not convinced that this was a very final draft. We see numerous inconsistencies in this prayer, making it awfully hard to give much weight to its use of pronouns. It is, IMO, better to rely more heavily upon what we have been given in LOTR (ie. Moria Gate Inscription) which we know Tolkien carefully considered.

Nominative Pronouns

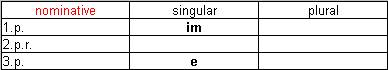

We only have two clear examples of nominative pronouns:

That makes reconstructing the nominative forms rather difficult. The problem being that both the 1.p.s is seemingly irregular; which does not lend itself to easy manipulation and stable conclusions. It may be that the irregularity of the i and the irregular m (where we seem to have n attested in every other case) are in some way related to the irregularity in general of these forms (perhaps it may be directly tied into phonological evolution of the pronouns from CE where the n may have become assimilated in some way. In either case it is clearly irregular). Now seeing the, until now, regular form of 3.p.sg., we might expect that nominative is formed by e- plus the characteristic vowel. This we do not find, which is, with careful thought, to be expected. Instead we see simply e (which might correspond to în, also not using any characteristic consonant). This lack of a characteristic consonant seems to correlate quite well with Sindarin verb conjugations, in which we see no ending in the 3.p.s.

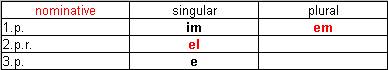

Now we might take a look at the conjugational/pronominal endings to fill in the other gaps. The attested endings are:

The 1.p. (sg. and pl.) fit into this concept perfectly. What about the unkown 2.p.s. forms though? While we have the ending –ch attested in the “Turin Wrapper” this phrase is, unfortunately, not translated for us (technically it isn’t published yet). I still believe that it is a viable pronominal ending though, along with what apears to be an alternate form –g. David Salo says that these forms are attested but have not yet been published. So then which should we use? Since we really only have an example of –ch, and this example seems to be in reference to a single person (assuming that the assumed translation is correct) I think we can venture to guess that this form may have been used for the 2.p.s. pronouns. This might suggest that –g is a plural form, but since we don’t have any material at hand to work with, the use of –g would be rather speculative at this time. Assuming that –ch is the correct form to use, we must look at what its development might have been. In old sindarin, –kke would, because of the loss of the final vowel and shift form kk>ch, give us the necessary form for the nominative pronoun; affixing as usual an e- before this characteristic consonant. In the dative, however, we would see a different form. When kk appears at the beginning of an Old Sindarin word, it would yield c-. This would therefore give us a dative form of cen in relation to the other attested forms men, ten. From this form it is simply a matter of extrapolation to produce the lenited possessive, accusative and also the long dative and reflexive dative forms for the 2.p.s.

Now what do we do about a possible 2.p.p. form? While it certianly may be that –g was inteded to take this place, with –ch being the 2.p.s. form, we see no evidence in Sindarin that such a 2.p.p. form even exists. Until more text is published, the best thing, and really the only thing, for us to do is assume that the 2.p.s. and 2.p.p. forms are identical to each other (as in English). This is however, pure speculation

Where now do the forms le, lîn fit in? Given that the attested uses of le and lîn are used when addressing the Valar or higher, I think it would be a safe assumption that Sindarin possesses both reverential and familiar pronoun forms.

Now, solely using the 3.p.pl. pronominal suffix –r, we can reconstruct all the missing pronouns for this form (assuming that the above named assumptions are not entirely wrong).

Let us now turn, to our reconstructed chart:

Note: The possessive and Accusative are both “pre-lenited”. Do not lenit these pronouns a second time.

Other Pronouns

General Reflexive Pronoun – înDemonstrative Pronouns/Adjectives – sen (this), sin (these)

• The use of în. This pronoun seems to be a general reflexive pronoun that can be used in place of the normal possessive pronouns. If this is the case, we would expect this pronoun to be used when referring to actions that affect oneself or the subject of the sentence (as opposed to some other person). This is similar to “the man drank his juice” problem. Does this mean “the man drank his own juice”? Or does it mean “the man drank the person across the room’s juice”? This reflexive pronoun seems to refer back to the subject of the sentence. Let’s look at some examples from the Kings Letter:

– Ar e aníra ennas suilannad mhellyn în

– ar Eirien sellath dîn

– ar Baravorn, ionnath dîn

It is important to keep in mind that we have two different people being discussed in this letter (both in the third person!). The King Elessar, and Sam (Perhael). The first sentence is used in reference to the king himself, and is believed to be reflexive. The final two are used in reference to Sam, who is essentially “the other man across the room” from our juice problem. Clearly these pronouns are not being used in reference to the King. I therefore think it is safe to conclude that în is a general reflexive possessive pronoun.

• We also find the demonstrative pronoun hin in the corpus in the Moria Gate Inscription; Celebrimbor o Eregion teithant i thiw hin. Due to its adjectival use, we would expect this form to be lenited and pluralized (in accordance with plural noun tiw). We can therefore suppose the un-mutated form to be sin “these”, and the singular form to be sen “this”.

Concerning the Noldorin Pronouns

Ha, ho, he – I do not include these pronouns and their various given forms in this chart because I am not convinced that they made it into mature Sindarin. These pronouns have differing forms for masculine, feminine, and neutral genders, where we seem to have evidence in Sindarin of only two: m/f with neutral only appearing in 3.p (in which instances these pronouns behave unlike the m/f). Secondly, these pronouns do not fit very well with the overall phonological scheme that we have here devised (assuming that it is at least partially correct). Perhaps future publications will prove one way or the other.Short Dative vs. Long Dative ?

• We now come to a somewhat serious problem. What do we do now that we have two separate dative forms? Which one does one use? The corpus seems to indicate that it is possible to do two things:– Use a short dative and place it before the verb as we see Tolkien do numerous times in the corpus. These forms seem to be used mostly when there is an implied direct object (ie. “To thee I sing”).

– Use a long dative and have it follow the verb. These forms seem to follow the direct object.

It seems very feasible then that we could see either form in a sentence. It is also very likely that we would see the short dative form used when forming other noun cases in Sindarin via prepositions. In these cases, the pronoun would acquire whatever mutation the preposition would cause. Only the context that you use such a word in will determine which form to use.

Reflexive Datives?

• We also seem to have reflexive dative forms in Sindarin. These are used to express such ideas as “for myself”, “for themselves”, “for itself” etc. The only attested form that we have from the corpus is anim “for my self”. This is quite clearly the nominative form im “I” plus the dative pronoun an “to, for”. If we follow this general pattern we can reconstruct what the other various reflexive forms may have been.A last guess

• We have the example of a suffixed possessive pronoun, guren = gûr nîn namely. As also Ryszard Derdzinski suggests I think this might be (if Tolkien did not drop this idea anyway) a hint that the characteristic consonant can be used as a suffix (after –e) to work as possessive too. These are very speculative forms, and should be treated as such. Nevertheless, I do believe that the general theory holds water, so it would not be disastrous to use such a form on a composition. It may be that these forms are used when a possessive is in the nominative (ie. “my heart tells to me”). So to stay with the given example I expect:guren – my heart; gurech – your heart; gurel – thy heart; gure (gured ?) – his/her heart; gures/ guras– its heart (n); gurais – their heart (n); gurem – our heart; gurer – their heart

Aaron Shaw (Gildor-Inglorion)

[email protected]

http://www.councilofelrond.com

Florian “Lothenon” Dombach

[email protected]

http://www.mellyn.de.vu

Special Thanks To: Taramiluiel and Elena_s_g ……. 3-19-03