The lands of Rohan

Rohan was a land of grassy plains and low hills, of herdsmen and horsemen. It came to be divided into a number of regions – the Westfold, the Eastfold, Eastemnet, Westemnet, and the Wold:

– Westfold – the main population centre of the land. Includes Edoras (site of the Muster of Edoras), Dunharrow and Harrowdale, and the Hornburg (site of the Muster of the West-mark) and Helm’s Deep.

– Eastfold – the site of the Muster of the East-mark. Includes Aldburg.

– Eastemnet – little is known

– Westemnet – little known

– The Wold – little known

Several good descriptions of the land and its flowing plains are given in “The Two Towers”.

“green flowed over the wide meads of Rohan; the white mists shimmered in the water-vales; and far off to the left, thirty leagues or more, blue and purple stood the White Mountains, rising into peaks of jet, tipped with glimmering snows, flushed with the rose of morning.” (The Riders of Rohan)

“At the bottom they came with a strange suddenness on the grass of Rohan. It swelled like a green sea up to the very foot of the Emyn Muil. The falling stream vanished into a deep growth of cresses and water-plants, and they could hear it tinkling away in green tunnels, down long gentle slopes toward the fens of Entwash Vale far away. They seemed to have left winter clinging to the hills behind. Here the air was softer and warmer, and faintly scented, as if spring was already stirring and the sap was flowing again in herb and leaf.” (The Riders of Rohan)

“they came to long treeless slopes, where the land rose, swelling up towards a line of low humpbacked downs ahead … Far away to the left the river Entwash wound, a silver thread in a green floor” (TTT, The Riders of Rohan)

The borders of the Riddermark

Third Age

The boundaries of the land were set out clearly in “Unfinished Tales, Cirion and Eorl”:

“in the West the river Angren [Isen] from its junction with the Adorn and thence northwards to the outer fences of Agrenost [Isengard], and thence westwards and northwards along the eaves of Fangorn Forest to the river Limlight … In the east its bounds were the Anduin and the west-cliff of the Emyn Muil down to the marshes of the Mouths of Onodló [Entwash], and beyond that river the stream of the Glanhír [Mering Stream] that flowed through the Wood of Anwar to join the Onodló; and in the south its bounds were the Ered Nimrais as far as the end of their northward arm, but all those vales and inlets that opened northwards were to belong to the Éothéod, as well as the land south of the Hithaeglir that lay between the rivers Angren and Adorn.” (Unfinished Tales, Cirion and Éorl)

In the pact between Cirion and Eorl, Isengard was kept as Gondorian, with the Mark stopping some two miles south of the gates. The border was marked with a wall and dyke.

Originally only a small part of the Wood of Anwar was included in the settlement for the Éothéod, with Cirion declaring the Hill of Anwar to be a hallowed place of both peoples. Both the Stewards and the Éothéod shared responsibility for its guard and maintenance. However, through time, the hill’s wardens started to come more and more from the Eastfold, and eventually, by custom, the Wood became part of the Mark. The Hill they called Halifirien, and the Wood, the Firienholt.

Fourth age

One account in HoME (The Peoples of Middle-earth – The Making of Appendix A (III) The House of Eorl – version III) suggests that in Éomer’s realm, the Mark was extended greatly. To the west it grew beyond the Gap of Rohan as far as the Greyflood and the sea-shores between the Greyflood and the Isen, and to the north it grew to the borders of Lothlórien.

Westfold

The Westfold, a land of fields and dales stretching down to the White Mountains, was the most important part of the Mark in terms of population and habitation. There were settled dwellings scattered about the feet of the White Mountains, as well as in the glens and valleys of the south. It contained a number of places discussed in detail in the books – Edoras, Meduseld, Helm’s Deep, Harrowdale, Dunharrow and the Fords of Isen. These are described below.

The people of the area went only to the northern bounds of the Westfold if need drove them, for there were the eaves of Fangorn and the menace of Isengard.

Edoras

Edoras was the “capital” of Rohan, and the main base for the First Marshal of the Mark and his Muster of Edoras. It was situated on a lonely foothill that stood out from the White Mountains like a sentinel.

Legolas gives a description of the town, making it seem almost like something from an old fairy tale:

“I see a white stream that comes down from the snows,” he said. “Where it issues from the shadow of the vale a green hill rises upon the east. A dike and mighty wall and thorny fence encircle it. Within there rise the roofs of houses; and in the midst, set upon a green terrace, there stands aloft a great hall of Men. And it seems to my eyes that it is thatched with gold. The light of it shines far over the land. Golden, too, are the posts of its doors.” (TTT, King of the Golden Hall)

Before the gates of the town were the barrows of the kings of old, seven on the left (eight after Théoden’s death), nine on the right. On the grass-covered mounds were simbelmynë that bloomed all year round.

The burial chambers themselves were stone, and contained the body as well as arms and other fair things belonging to the kings. Over the stone chambers were raised great mounds, covered with turf. The west side mounds were those of Eorl, Brego, Aldor, Fréa, Fréawine, Goldwine, Déor, Gram, and Helm; and the east side mounds those of Fréalaf, Léofa, Walda, Folca, Folcwine, Fengel, Thengel, and Théoden. Fourth Age tales said that sometimes a river of gold or silver flowed from Théoden’s Howe.

It appears that Tolkien originally meant for Edoras to have only one mound, for in Letters #93 (24th December 1944), he mentions the simbelmynë-covered “Great Mound of Rohan”.

The actual town of Edoras was situated on the mound of the hill, behind wide windswept walls. Entrance was via guarded gates:

“The dark gates were swung open. The travellers entered, walking in file behind their guide. They found a broad path, paved with hewn stones, now winding upward, now climbing in short flights of well-laid steps. Many houses built of wood and many dark doors they passed. Beside the way in a stone channel a stream of clear water flowed, sparkling and chattering. At length they came to the crown of the hill. There stood a high platform above a green terrace, at the foot of which a bright spring gushed from a stone carved in the likeness of a horse’s head; beneath was a wide basin from which the water spilled and fed the falling stream. Up the green terrace went a stair of stone, high and broad, and upon the topmost step were stone-hewn seats. There sat other guards, with drawn swords laid upon their knees.” (TTT, King of the Golden Hall)

The terrace at the stair’s head was paved, and the doors to Meduseld were heavily barred and opened inwards.

In an early draft in “The Treason of Isengard”, the outer appearance of Meduseld was described:

“Before Théoden’s hall there was a portico, with pillars made of mighty trees hewn in the upland forests and carved with interlacing figures gilded and painted. The doors also were of wood, carven in the likeness of many beasts and birds with jewelled eyes and golden claws.”

Christopher Tolkien considered it curious that this description did not make the final text, having been in the fair copy manuscript, and he thought that it may have got lost during redrafting and reordering.

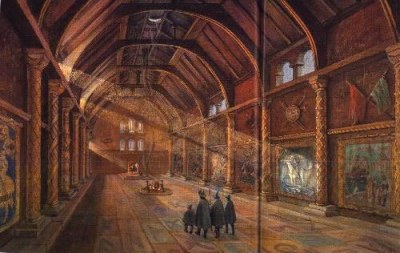

At the top of the hill stood Meduseld, the Golden Hall.

“The hall was long and wide and filled with shadows and half lights; mighty pillars upheld its lofty roof. But here and there bright sunbeams fell in glimmering shafts from the eastern windows, high under the deep eaves. Through the louver in the roof above the thin wisps of issuing smoke, the sky showed pale and blue.” (TTT, King of the Golden Hall)

There were woven cloths on the wall, showing figures of ancient legend. One showed Eorl as a young man on a white horse, blowing a horn and with his hair flying in the wind. Foaming water, green and white, rushed and curled about his horse, Felarof’s, knees.

The floor was paved with stones of many colours, carved with runes and strange devices. The pillars were also carved, covered with now-dulled golds and half-seen colours.

In the centre of the Hall was a wood-fire set on a long hearth, the smoke leaving the Hall by a louver far above. Facing north, towards the doors, was a dais with three steps, and in the middle of the dais was a great gilded chair, Théoden’s throne.

The windows were simple unglazed slits under the eaves, and it is likely that the whole building was one great space. Even Théoden was unlikely to have had any private dwelling, unless he had a sleeping ‘bower’ in a separate small ‘outhouse’.

Meduseld also contained an armoury.

Helm’s Deep / Hornburg / Aglarond

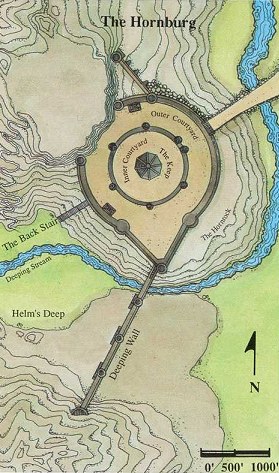

The Hornburg fortress complex, situated at the mouth of Helm’s Deep was the principal defence-point of the West-mark. It was the seat of the Second Marshal of the Mark – in the time of LotR, this was Théodred and then Erkenbrand.

Until the time of Helm Hammerhand the fortress was known as Suthberg, and then, after his heroics, it was renamed to honour the fallen king.

To get to the Hornburg from Edoras, there was a beaten road running along the foothills of the White Mountains in a north-westerly direction, crossing small swift streams by fords before reaching Helm’s Deep.

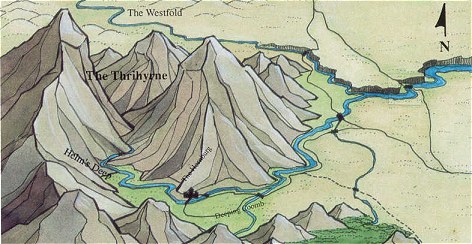

“Still some miles away, on the far side of the Westfold Vale, lay a green coomb, a great bay in the mountains, out of which a gorge opened in the hills. Men of that land called it Helm’s Deep, after a hero of old wars who had made his refuge there. Ever steeper and narrower it wound inward from the north under the shadow of the Thrihyrne, till the crowhaunted cliffs rose like mighty towers on either side, shutting out the light.” (TTT, Helm’s Deep)

The Hornburg complex consisted of a number of fortifications and natural features, as described below:

– Deeping-coomb

The Deeping-coomb was a low valley in front of Helm’s Deep, containing both the Deeping Stream and the main thoroughfares of the region. It was a rich vale and contained many homesteads, haystacks and trees.

– Helm’s Gate and the Hornburg

“At Helm’s Gate, before the mouth of the Deep, there was a heel of rock thrust outward by the northern cliff. There upon its spur stood high walls of ancient stone, and within them was a lofty tower. Men said that in the far-off days of the glory of Gondor, the sea-kings had built here this fastness with the hands of giants” (TTT, Helm’s Deep)

Not only was the Hornburg said to be built by the hands of giants, it was also said to have never been fallen to assault.

The buildings and fortifications of the Hornburg were described in great detail by Tolkien, both in word and in picture, and we can say very clearly what this great fortress looked like.

As one came up the Deeping-coomb, one would see the Hornrock and its fortress on the right, jutting out from the north wall of the mountains, and then a long wall joining the fortress to the southern cliff. This was the Deeping Wall, and was broken in only one place, a culvert allowing the Deeping Stream to flow through out into the Deeping-coomb and on into the Westfold Vale.

The Deeping Wall was 20 feet high, and wide enough for four men to walk abreast along it. The overhung top was sheltered by a parapet which only a tall man could look over, and which was slit with arrow-clefts. It was smooth externally, and its stones were set so that no foothold could be found.

The Wall could be reached from the fortress by a stair running down from a door in the outer court of the Hornburg, and also from three flights of steps leading up from the Deep behind the Wall.

In early versions of the mythology, instead of the Deeping Wall, Helm’s Dike was the Hornburg’s only protection. This was simply an ancient trench and raised rampart of great stones scored across the coomb, two furlongs below Helm’s Gate. The Deeping Stream and the road from the Hornburg passed through a mile-wide breach in it. Above the Dike was a sloping sward up to the fortress. In the earliest account, the fastness consisted of only the sudden natural fall in the land across the mouth of the coomb, fortified with a parapet of great stones. At that point, it had three breaches, which Tolkien called also “inlets”, as if there were more of a natural feature than man-made.

The main entrance to the Hornburg was almost on the opposite side of the Hornrock from the Deeping Wall, and consisted of a causeway and ramp leading to arched great gates. There was an iron postern-door in the outer court, with a narrow path running round southerly towards the great gates. The fortress also had a rear entrance, with a wide staircase leading from the Deep up onto the Hornrock.

Within the outer courtyard was another wall and then the inner courtyard, with the keep in its centre. The keep contained a high tower (the “king’s tower”) with narrow windows looking out upon the vale. In the tower was the horn or trumpet of Helm Hammerhand, which when blown, echoed through the whole Deep.

– Burial mounds

After the Battle of the Hornburg, two mounds were raised in the middle of the field in front of the Rock. That containing the fallen from the East Dales was on one side, and that containing Westfold men on the other. In a grave alone under the shadow of the Hornburg Háma was laid to rest.

– Death Down

Again after the Battle of the Hornburg, a huge pit was discovered delved by the huorns one mile below the Dike. Stones had been piled over it into a tall, black hill. No grass would grow there, and no man ever set foot there.

– Aglarond

Aglarond, the Glittering Caves, were situated in the mountains behind Helm’s Deep. There were entrances into the caverns from the Deep, and also secret ways from the caverns up on to the hills.

The description of the caves is best left to Tolkien:

“immeasurable halls, filled with an everlasting music of water that tinkles into pools, as fair as Kheled-zâram in the starlight.

And, Legolas, when the torches are kindled and men walk on the sandy floors under the echoing domes, ah! Then, Legolas, gems and crystals and veins of precious ores glint in the polished walls; and the light glows through folded marbles, shell-like, translucent as the living hands of Queen Galadriel. There are columns of white and saffron and dawn-rose, Legolas, fluted and twisted into dreamlike forms; they sprung up from many coloured floors to meet the glistening pendants of the roof: wings, ropes, curtains fine as frozen clouds; spears, banners, pinnacles of suspended palaces! Still lakes mirror them: a glimmering world looks up from dark pools covered with clear glass: cities, such as the mind of Durin could scarce have imagined in his sleep, stretch on through avenues and pillared courts, on into the dark recesses where no light can come. And plink! a silver drop falls, and the round wrinkles in the glass make all the towers bend and waver like weeds and corals in a grotto of the sea. Then evening comes: they fade and twinkle out; the torches pass on into another chamber and another dream. There is chamber after chamber, Legolas; hall opening out of hall, dome after dome, stair beyond stair; and still the winding paths lead on into the mountains’ heart. Caves! The Caverns of Helm’s Deep! Happy was the chance that drove me there! It makes me weep to leave them.” (TTT, The Road to Isengard”)

Harrowdale / Dunharrow

Dunharrow has to be the other best documented place in Rohan. We have not only detailed descriptions of it from RotK, but also a series of writings and sketches showing the evolution of Tolkien’s ideas for the fastness.

– Harrowdale

Dunharrow was situated in the narrow valley of Harrowdale, hollowed out by the Snowbourn flowing down from the Starkhorn at the end of the valley. Edoras was at situated at the head of the Harrowdale valley, and near the town, the Snowbourn could easily be forded.

Harrowdale was described in RotK, and well as earlier drafts of the mythology:

“The road now led eastward straight across the valley, which was at that point little more than half a mile in width. Flats and meads of rough grass, grey now in the falling night, lay all about, but in front on the far side of the dale Merry saw a frowning wall, a last outlier of the great roots of the Starkhorn, cloven by the river in ages past. (RotK, The Muster of Rohan)

“The long vale of Harrowdale. Dark on the right loomed the vast tangled mass of Dunharrow, its great peak now lost to sight, for they were crawling at its feet. Lights twinkled before them on the other side of the valley, across the river Snowborn white and fuming on its stones. They were come at last at the end of many days to the old mountain homes of folk forgotten – to the Hold of Dunharrow.” (The War of the Ring)

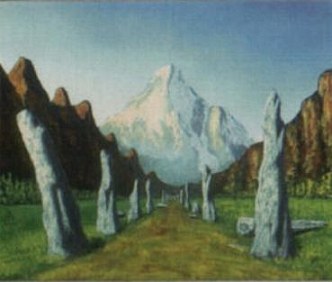

– Dunharrow

Dunharrow was a place of superstition and mystery for the Rohirrim, being adorned by the Púkel-men, monolithic reminders of the creators of the fastness, and leading to the Dimholt and the Paths of the Dead. The first of the Rohirrim to use Dunharrow as a refuge-fort was Aldor the Old.

The hold of Dunharrow consisted of a large mountain-field, the Firienfeld, and the wood of Dimholt.

The road from the valley to Dunharrow was described in RotK:

“He was on a road the like of which he had never seen before, a great work of men’s hands in years beyond the reach of song. Upwards it wound, coiling like a snake, boring its way across the sheer slope of rock. Steep as a stair, it looped backwards and forwards as it climbed. Up it horses could walk, and wains could be slowly hauled; but no enemy could come that way, except out of the air, if it was defended from above. At each turn of the road there were great standing stones that had been carved in the likeness of men, huge and clumsy-limbed, squatting cross-legged with their stumpy arms folded on fat bellies. Some in the wearing of the years had lost all features save the dark holes of their eyes that still stared sadly at the passers-by” (RotK, The Muster of Rohan)

Hundreds of feet above the valley, the road passed into a cutting between two rock walls, and went up a further short slope out onto a wide upland, the Firienfeld.

– Firienfeld

The Firienfeld was a green mountain-field of grass and heath, high above the deep-delved courses of the Snowbourn. It was divided into two by a double line of unshaped standing stones that vanished into the trees at the back of the field. The southerly side of the field was wider, and it was there that the tents of most of the Riders were pitched in RotK, close to the cliff. Théoden’s pavilion and Merry’s tent were pitched with a smaller amount of the Rohirrim on the north side of the avenue.

Behind the Firienfeld were three peaks – snow-covered and jagged Starkhorn to the south, saw-toothed Irensaga [Ironsaw] to the north, and Dwimorberg – the grim, black walled, Haunted Mountain. The mountains all rose out of steep slopes of sombre pines.

Dunharrow was always considered a place of secrets, an ancient holdfast made by long-forgotten men:

“Such was the dark Dunharrow, the work of long-forgotten men. Their name was lost and no song or legend remembered it. For what purpose they had made this place, as a town or secret temple or a tomb of kings, none could say. Here they laboured in the Dark Years, before ever a ship came to the western shores, of Gondor of the Dúnedain was built, and now they had vanished, and only the old Púkel-men were left, still sitting at the turnings of the road.” (RotK, The Muster of Rohan)

– The Dimholt and the Paths of the Dead

“If there be in truth such paths,” said Théoden, “their gate is in Dunharrow” (RotK, Passing of the Grey Company)

The Dimholt [Firienholt] was a dark wood at the back of the Firienfeld, and the path from the field into its shadows was lined with ancient stones. Under the black trees, in a clearing, was a single stone “like a finger of doom”, and beyond that was the Dark Door, leading into Dwimorberg and the Paths of the Dead:

“The horses would not pass the threatening stone, until the riders dismounted and led them about. And so they came at last deep into the glen; and there stood a sheer wall of rock, and in the wall the Dark Door [Gate of the Dead] gaped before them like the mouth of night. Signs and figures were carved above its wide arch too dim to read, and fear flowed from it like a grey vapour.” (RotK, Passing of the Grey Company)

The Eastfold (and the Folde)

The Eastfold was the home of Eorl the Young’s original seat, Aldburg, situated close to Anorien and Halifirien. During the time of LotR, Éomer was the lord of the Eastfold, and also used Aldburg as his seat.

“The Folde was part of the King’s Lands, but Aldburg remained the most convenient base for the Muster of the East-mark.” (Unfinished Tales, “Appendix (i)” in “The Battles of The Fords of Isen”)

Westemnet

Little is known of the region of Westemnet, with the only reference to the area being that of Éomer telling Aragorn that battle had come even to the Westemnet (TTT, Riders of Rohan).

Note: the West-mark is not a geographical region, nor the same as Westemnet. It was simply a military term, used to describe the areas of the Muster of Rohan.

Eastemnet

Eastemnet was a region where herds and studs were widespread, with herdsmen living a nomadic existence through all seasons in camp and tents.

The Eastemnet included the East Wall of Rohan, the escarpment leading down from the Emyn Muil:

“The ridge upon which the companions stood went down steeply before their feet. Below it twenty fathoms [120 feet / 37m] or more, there was a wide and rugged shelf which ended suddenly in the brink of a sheer cliff: the East Wall of Rohan. So ended the Emyn Muil, and the green plains of the Rohirrim stretched away before them to the edge of sight.” (TTT, The Riders of Rohan)

“Here the highlands of the Emyn Muil ran from North to South in two long tumbled ridges. The western side of each ridge was steep and difficult, but the eastward slopes were gentler, furrowed with many gullies and narrow ravines. All night the three companions scrambled in this bony land, climbing to the crest of the first and tallest ridge, and down again into the darkness of a deep winding valley on the other side.” (TTT, The Riders of Rohan)

References to general conditions in Eastemnet appear only when Gandalf is talking of Shadowfax:

“The ground is firmer in the Eastemnet, where the chief northward track lies” (TTT, The White Rider)

“They came upon many hidden pools, and broad acres of sedge waving above wet and treacherous bogs; but Shadowfax found the way, and the other horses followed in his swath.” (TTT, The White Rider)

Note: the East-mark is not a geographical region, nor the same as Eastemnet. It was simply a military term, used to describe the areas of the Muster of Rohan.

The Wold

The Wold was another little known region, being described as having windy uplands in TTT, “The Riders of Rohan”. In its north-east was the Field of Celebrant.

Rivers of Rohan

The main rivers of the Mark were the Snowbourn, the Isen and the Entwash. The Snowbourn rose in the gorges of the Starkhorn, and flowed down through Harrowdale to meet the Entwash 12 leagues east of Edoras in an area of willow thickets.

There are some beautiful descriptions of the Entwash and its confluence with the Snowbourn:

“the stream … ran down swiftly into the plain, and beyond the feet of the hills turned across their path in a wide bend, flowing away east to feed the Entwash far off in its reed-choked beds. The land was green: in the wet meads and along the grassy borders of the stream grew many willow-trees.” (TTT, King of the Golden Hall)

“the river wandering deep in dim thickets of reed and rush” (TTT, The Riders of Rohan)

Maybe the most important feature of the rivers in Rohan were the Fords of Isen, the only places where a large troop could cross the River Isen. There were the scene of two important battles in the War of the Ring.

The Isen came down into Rohan from its source above Isengard, and as it reached the flat plains, it slowed in its path, turning westward and continuing on through the land. Just before its westward bend were the Fords, where the river passed in two streams around a large eyot, and where the bed was a stable shelf covered with pebbles and stones.

“The road dipped between rising turf-banks, carving its way through the terraces to the river’s edge, and up again upon the further side. There were three lines of flat stepping-stones across the stream, and between them fords for horses, that went from either brink to a bare eyot in the midst.” (TTT, The Road To Isengard)

By the times of the War of the Ring, the river bed at the fords was almost dry, just a bare waste of shingles and grey sand; but after Isengard fell, water flowed down again through the river, and the fords refilled.

Also after the Battles at the Fords of Isen, a burial mound was raised on the eyot, set about with many stones.

Appendix – Evolution of Dunharrow

In HoME (most importantly, in “The War of the Ring”), Tolkien’s notes and manuscripts give us a clear idea of the evolution of Dunharrow, from its early incarnation as a feasting hall set into cliffs, to the more simple windswept plateau of RotK.

In the earliest versions, the rock at the back of the plateau was full of caves cut and moulded by both nature and man. Legend said that was a dwelling, and perhaps a holy place, of forgotten men in the Dark Years.

“Here the Eorlingas had made a stronghold, but they were not a mountain folk, and … they passed down the vale and built Edoras at the north of Harrowdale. But ever they kept the Hold of Dunharrow as a refuge, There still dwelt some folk reckoned as Rohir, and the same in speech, but dark with grey eyes. The blood of the forgotten men ran in their veins.” (The War of the Ring, Book Five Begun and Abandoned)

In the next set of writings:

“the Hold – the mountain homes of long forgotten folk. Dim legends only now remembered them. Here they had dwelt [and had made a dark temple a temple and holy place in the Dark Years] … built a refuge ……. [?that no enemy] could take. There was a wide upland [field > ?slope] set back into the mountain – the lap of Dunharrow. Arms of the mountain embraced [it] except for a space upon the west. Here the [?green bay] fell over a sheer brink down into Harrowdale. A winding path led up. Behind the sheer walls of the vale were …. caves – made by ancient art” (The War of the Ring, Book Five Begun and Abandoned)

Here we have emphasis placed on the rock caves at the end of the Firienfeld, with the caves being probably used as a temple and a holy place. The Púkel-men do not yet exist. There is also a torch-lit stone hall, where the feast in the Muster was held.

But still, consistent through everything, is the idea that Dunharrow is somehow mysterious and sacred, the product of age-old men no longer living. However, in one or two of these earliest versions, there is actually one old man left in the caves, but he dies soon after he is discovered, and does not disclose any information about the place.

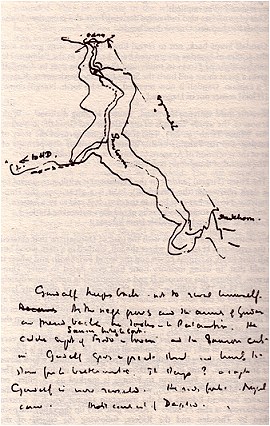

From these earliest writings, we then have to turn to “The End of the Third Age” for the next bits of information about Dunharrow – two sketches that were left out of “The War of the Ring”.

– Dunharrow I (“The End of the Third Age”)

A sketch by Tolkien, that was never put into words. In this idea, a path wound up from the valley and passed near the top of the cliff through a great door, entering a steep tunnel coming out on the flat land above. A single menhir was present, but there is no sign of the Púkel-men.

|

|

– Dunharrow II (“The End of the Third Age”)

In Dunharrow II, we see the evolution of a more normal shape for the road from the vale to the plateau. There are stones on the bends of the road, and something approaching the stone-lined avenue across the plateau.

– Manuscript F

The next stage is that of Manuscript F, discussed in “The War of the Ring”:

“the road passed between walls of rock and led them out onto a wide upland: the Lap of Starkhorn men called it … a green mountain-field of grass and heath above the sheer wall of the valley that stretched back to the feet of a high northern buttress of the mountain. When it reached this at one place it entered in, forming a great recess, clasped by walls of rock that rose at the back to a lofty precipice. More than a half-circle this was in shape … its entrance a narrow gap between sharp pinnacles of rock that opened to the west. Two long lines of unshaped stones marched from the brink of the cliff … towards it, and … in the middle of its rock-ringed floor under the shadow of the mountain one tall menhir stood alone. At the back under the eastern precipice a huge door opened, carved with signs and figures worn by time that none could read. Many other lesser doors there were at either side, and peeping holes far up in the surrounding walls.

This was the Hold of Dunharrow: the work of long-forgotten men. No song or legend remembered them, and their name was lost. For what purpose they had made this place, a town, or secret temple, or a tomb of hidden kings, no one could say. … only the old Hocker-men [later > Pookel-men] were left, still sitting at the turnings of the road.”

Here, the idea of a feast-hall in a cavern is still firmly in place. The end of the hall rises to a high platform of rock, fires of pinewood are lit down the centre between the pillars, and the smoke escapes through invisible fissures. Torches blaze on wall and pillar, and 3000 men could stand in there.

– Synopsis II

Synopsis II has the Firien [Firgen, Halifirien] as a hill surrounded by a dark pinewood, the Firienholt. In the hill is a great cave, the Dunharrow. No one had ever been in the cave, which was said to be a haliern, and to contain some ancient relic of old days.

A small sketch-map on the same paper as Synopsis II shows Edoras at the head of the long Harrowdale valley. While in LotR, Théoden’s path crossed the Snowbourn itself, in these early versions the path crosses the mountain stream before its conjunction with the Snowbourn.

– Manuscript H

Manuscript H was the last version discussed in “The War of the Ring”. The Firien is here a hill clothed in a dark wood, but with a bare summit. The wood is known as the Firienwood, but still none in living memory had ever dared enter.

The idea that Dunharrow is a cavernous hold opening onto the green mountain-field is by then abandoned, Christopher Tolkien saying that

“my father at the same time moved its site far down the valley towards Edoras, and made it a cave or caves in a hill (“Firien”) some 50 miles or so from the Starkhorn” (The War of the Ring)

Later on, the Firien becomes Dwimorberg, and the Firienholt, Dimholt, and the Dunharrow we see in LotR starts coming into view.

References

– The Two Towers

– The Return of the King

– The Treason of Isengard (HoME 7)

– The War of the Ring (HoME 8)

– The End of the Third Age (addition to HoME 9)

– The Peoples of Middle-earth (HoME 12)

– Unfinished Tales

– The Letters of JRR Tolkien

Maps of the Hornburg and Helm’s Deep © Middle-earth Quest