07 Future, aorist

Just like English, Quenya can be said to have two tenses that are used to describe actions in the present; the present tense (see Lesson 5), which is used for ongoing actions, and the so called aorist, which is used for “general” or “timeless” actions.

The aorist tense of a-stem verbs looks the same as the verb stem.

Example harya- (stem: to have) > harya (aorist: has, have).

The aorist tense of primary verbs is formed by adding -i to the stem, *but* this “i” changes to “ë” unless another ending follows after it.

Example mat- (to eat) > matë (eats, eat)

Just as with the previously discussed tenses, “-r” is added when the verb has a plural subject.

Example: “i laman matë” (the animal eats), but “i lamni matir” (the animals eat).

Notice that the “real” aorist ending “-i-” is visible here, because of the added plural ending “-r”.

The future tense

The future tense is used to describe actions in the future; things that are going to happen. The future tense of both kinds of verbs is formed by adding the ending “-uva”. The final “-a” of a-stems is dropped when the future tense ending is added.

Examples: harya- > haryuva (will have); mat- > matuva (will eat).

The plural is formed by adding the plural marker “-r”.

Example: “i roquen haryuva rocco” (the knight will have a horse), but “i roqueni haryuvar rocco” (the knights will have a horse). Or, if the king is generous and the knights will each have a horse of his own; “i roqueni haryuvar roccor” (the knights will have horses).

***

Lesson 7 Vocabulary list

feuya- “abhor”

tur- “rule, control, govern”

fir- “die”

mitta- “enter”

sí “now”

mal “but”

osto “town”

anga “iron”

telpë “silver”

nórë “country, land, nation”

vessë “wife”

venno “husband”

aran “king”

***

Tengwar Lesson 7

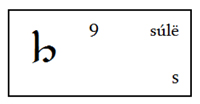

In this lesson we’ll continue to look at the s-sounds. An important tengwa that also denotes ‘s’ is:

If you remember our discussion of the difference between númen and noldo, then the relation between silmë and súlë is quite similar.

In Primitive Elvish súlë denoted the ‘th’-sound (still present in English) but it disappeared in Third Age Quenya and became pronounced as ‘s’. But, as with noldo, to write correct Quenya you have to write words that developed from a Primitive Elvish word with a ‘th’ still with súlë and not with silmë (the ordinary or the upside down variant make no difference). With a double ‘ss’ there’s no problem as in that case essë is always used.

Words with súlë can be recognized in the word lists as they have a thorn þ after them (this is an ancient English letter that denoted the ‘th’).

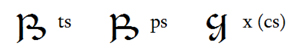

Sometimes silmë is abbreviated to a so called s-hook. This happens only when the ‘s’ immediately follows a ‘t’, ‘p’ or ‘c’ (and ‘cs’ is always shortened to ‘x’ in the Latin notation of Quenya):

The s-hook of ‘ts’ and ‘ps’ is only used if it’s the last tengwa of a word (but ‘x’ can be used everywhere in a word).