Love and War

After his final exams, Tolkien had to take up his commission with the Lancashire Fusiliers. He was posted to the 13th battalion as a Second Lieutenant, the lowest rank of officer. His training, which was meant to prepare him for life and war at the Front, began in July 1915, when he learnt to drill a platoon and attended military lectures. He bought a motorbike and, on weekend leaves, he rode over to visit Edith. He also began to grow a moustache.

In August 1915, he was moved to Staffordshire, and from then onwards his battalion was shifted round from camp to camp, in an apparently aimless manner. When Tolkien was not eating, doing trench drills, or having lectures, he was free to play bridge – a game he enjoyed. However, this was often accompanied by the sounds of ragtime on the gramophone – something he rather disliked. It was also important to Tolkien that he kept up with his academic studies, and so he spent some of his free time reading Icelandic.

Time passed slowly.

“These grey days wasted in wearily going over, over and over again, the dreary topics, the dull backwaters of the art of killing, are not enjoyable.”

In 1916, Tolkien decided to specialise in signalling, which involved learning the Morse Code, flag and disc signalling, message relay by heliograph and lamp, use of field telephones, and signal-rockets, as well as carrier-pigeon handling. Eventually he was appointed battalion signalling officer.

Marriage

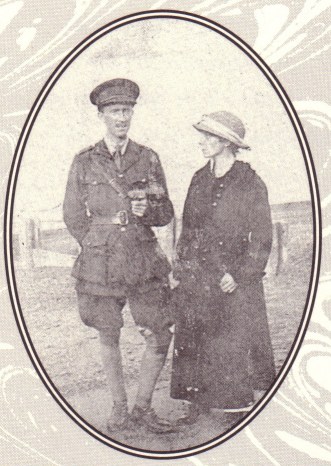

When it was clear that the battalion would soon leave for France, Edith and Tolkien decided to get married as both knew that there was a real possibility that he would never return. Edith was 27, Tolkien was 24, and for the first time in his life, Tolkien had a regular income from the Army. He asked Father Francis to transfer all of his share capital into his own name, and he also hoped to start getting income from his poetry – “Goblin Feet” had

been accepted by Blackwells for their annual volume of “Oxford Poetry”, and

Tolkien had also sent a selection of his work to Sidgwick and Jackson.

Tolkien went to Birmingham to see Father Francis to tell him about the marriage – but he couldn’t forget Father Francis’ opposition to their relationship, and in the end he didn’t mention the wedding. It was not until a fortnight before the ceremony that he finally wrote with the news. Father Francis wrote back a kind letter, wishing the couple every blessing and happiness, and saying that he wished to conduct the ceremony personally in the Oratory. Unfortunately, it had already been arranged that Father Murphy, Edith’s parish priest, would lead the wedding.

The wedding took place on the 22nd of March 1916, after early mass in Father Murphy’s church in Warwick. It was a Wednesday – the day of the week they were reunited in 1913. Edith panicked when she realised that she had to give her father’s name and profession in the marriage register, as she was illegitimate and knew nothing about her father. She ended up writing “Frederick Bratt” – an uncle, but left the profession section empty. She told Tolkien the truth immediately afterwards, but it only increased his feelings of tenderness towards her. The couple went for a one week honeymoon by train to Clevedon. During their time there, Edith and Tolkien visited the Cheddar Gorge caves, which were to become the inspiration for the Glittering Caves.

On returning from Clevedon, Tolkien settled Edith and Jennie in Great Haywood, in Staffordshire.

The Big Push

Embarkation orders came on 4th June 1916, and Tolkien set off for London, then to be sent to France. He arrived in Calais on the 6th June, and was taken to base camp at Étaples where he found that his entire kit had been lost, and he had to beg, borrow or buy replacements.

The nervous excitement of embarkation soon wore away into a weary boredom made worse by a total lack of knowledge of what was going on. To make things worse, Tolkien was transferred to the 11th Battalion where he found little convivial company. The junior officers were all very young, and the senior officers were all old professional soldiers who treated the junior officers as schoolboys playing at soldiers. However, through his batman, Tolkien got to know several of the ordinary soldiers very well. Years later, he wrote that Sam Gamgee was a reflection of the English soldier, which Tolkien recognised as far superior to himself in fortitude and loyalty.

After three weeks in Étaples, Tolkien’s Battalion set off for the Front. They were billeted in Rubempré, near Amiens. From that point onwards, every day was dominated by the booms, crashes and roars of the Allied bombardment of the German lines.

On the 30th June, Tolkien’s battalion was moved closer to the front line, but it was held back in reserve during the next series of attacks. On the 1st July, Rob Gilson went over the top with his Suffolk regiment. They had been told that the German defences had been pretty much destroyed, and the barbed wire cut, but as they approached the German positions, machine guns started to fire at them, and the regiment was quickly decimated.

Tolkien’s battalion was then moved to Bouzincourt – where it was easy for all the soldiers to see that the war was not going to plan. Troops were detailed for grave digging, and wounded soldiers were everywhere. In the one day that Tolkien moved to Bouzincourt, it has been estimated that 20,000 Allied soldiers were killed.

On the 6th July, the A company of the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers went into action, but still Tolkien and the B company stayed behind. Later that day, GB Smith arrived at Bouzincourt, uninjured. This proved to be a high point in Tolkien’s war as for the next few days they talked as often as they could, discussing poetry, the war and the future.

On Friday, 14th July, the B company finally went into action. There was bitter disillusionment for the signallers – including Tolkien – as they went on to the battlefield only to find out-of-order field telephones and a prohibition on the use of wires and Morse buzzers. During their time in the battle, they had to rely on lights, flags, runners and even carrier pigeons.

Tolkien’s experiences of the Somme battleground simply must have coloured his writings on Mordor. Corpses lay everywhere, mutilated, decaying and bloated. Desolation was all around as grass and crops had disappeared into a sea of mud. Trees were stripped all their leaves and bark, and stood proud from the flat landscape as scorched and burnt silhouettes. Tolkien later said that he never forgot the “animal horror” of trench warfare.

B company were attached to the 7th Infantry Brigade for their first day in action. They were to attack Ovilliers, a ruined hamlet still in German hands. The attack was unsuccessful, and many men were killed. Luckily, Tolkien was unhurt, and after 48 hours of constant battle, he was allowed to sleep. A day after that, he was relieved of duty, and allowed to return to Bouzincourt, only to be greeted with a letter from GB Smith saying that Rob Gilson was dead. Tolkien’s reply to his friend included the following:

“I do not feel a member of a complete body now.”

showing the anguish Tolkien must have felt on the loss of one of the TCBS.

But even after that, days continued following the same wearying pattern as the battalion took part in the storming of the Schwaben Redoubt. Soon Tolkien met up again with GB Smith, this time at Acheux. The day before Tolkien returned to the trenches, they had a meal together at Bouzincourt, coming under fire as they ate.

Tolkien remained unhurt until 27th October when he succumbed to trench fever at Beauval. He was transported to a nearby hospital, but then the next day he was taken to Le Touquet, on the French coast. On 8th November, he was shipped to England, and ended up in Birmingham, where he was reunited with Edith. Near the end of December, he was well enough to leave hospital, and he went to Great Haywood for Christmas. There he received a letter from Christopher Wiseman saying that GB Smith had died.

Only few days before he died, GB Smith had written to Tolkien, including what were to become prophetic words.

“May you say the things I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them.”

This letter made it clear to Tolkien that it was time to begin the great work that he had been meditating on for some time.